Standen's roots originate back to the reign of Queen Victoria!

Many of the older companies in our industry are associated with either a particular person or a particular product, or sometimes with both: Henry Ford and his first massed-produced tractor, the Fordson, or Harry Ferguson and his revolutionary hydraulic system, plus of course his little gray tractor. Even further back are Ransomes, who will always be associated with the development of the modern plough. Massey-Harris and the combine are inseparable, as are John McCormack and the binder.

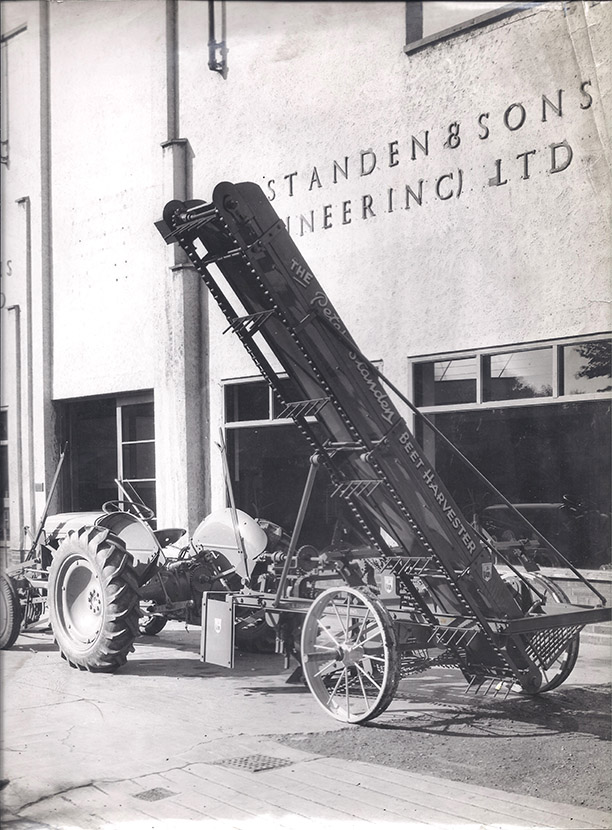

The name of Peter Standen is synonymous with British engineered potato and sugar beet machinery. Peter Standen is the man, who picked up the reins of his father’s development workshop to create Standen Engineering, and his name has adorned the sides of successive models of sugar-beet harvesters which entered service during the nineteen-fifties and sixties.

Peter Standen and Vic Gray in 1967:

This brief illustrated history will trace the development of the company since the war, which as with most agricultural companies a story of machines, and the people who made them.

The Early Days

We know there was a Samuel Frank Standen working as a blacksmith in West Street, St Ives, in Cambridgeshire in 1846. There had been a smithy on the site for several generations before Samuel picked up his first hammer as a boy, or pumped his first bellow, because by the nature of things the local blacksmith was a permanent feature of the farming community, son following father, and expecting his son to follow him. Samuel's own father Henry had taken over the business from his father Elias, who himself had moved up to Cambridgeshire from Sussex in the 1820's. No doubt Samuel expected his eldest son Frank to take over the business when it was time for him to forge his last horse-shoe.

History is hazy on the subject, but what is known is that Frank had a falling-out with his father, and as a result took himself off to Pig Lane in St Ives and started his own business. By 1906 he was filing for a patent on a fixed tine cultivator, so clearly he was showing signs of the inventiveness that he passed down in full measure to his son Peter.

Old Samuel died in 1911, but Frank was by then into his stride and had already registered his company F.A.Standen Ltd. During the twenties he took on various franchises, including Austin cars and lorries, and in 1934 was appointed the local dealer for John Deere and Case. Of course in those days farming was in terrible financial trouble, with many farmers walking away from their farms, as it was impossible to make a living. Fortunately East Anglia has always been a favoured agricultural area, and however bad things were Frank was able to make ends meet and to continue to pay his staff of five.

By 1936 his son Peter and brother Eric had joined their father and the name of the company was expanded to F.A.Standen & Sons Ltd.

Whilst Eric became more involved in the retail side of the business, Peter began experimenting with new designs of machine, and proved so apt that his father funded a new company, F.A.Standen & Sons (Engineering) Ltd, with Peter as the effective boss.

Frank and Peter Standen with executives of Massey-Ferguson at a Royal Show in the 1960's. Frank is on the left of the picture, Peter the right.

The War Years

When the government of the time realised war with Germany was almost inevitable money was directed back into farming, and only just in time too. The War years were what we now call a command economy, with the Ministry of Agriculture, or WarAg as it was called, dictating who grew what and where, who received the new machines that were coming across the Atlantic in the holds of merchantmen, and what price farmers would receive for their produce. Out of all this however came a healthy farming industry, which, once the War was over, was able to fill the bellies of the under-nourished people of Britain. Nor must it be forgotten that at this time most of Europe was close to starving, with ruined factories, displaced populations, and no money.

Against this background British agriculture was poised to take a giant leap forward, and in particular in the engineering sector. Once the benefits of America’s generous Marshall Aid programme filtered through there was an insatiable demand in Europe for mechanisation, for machines to replace human labour, for machines to drive up productivity. Thus any company in the position to design and manufacture such machinery was strongly placed to reap a growing reward as prosperity returned to exhausted countries.

One such company was Standen, with Peter Standen opening premises in the nearby city of Ely. It should be noted that by this time the dealer side of the business had switched from John Deere to Massey-Harris, and in due course took over the Ferguson franchise. These two brands in fact became one through the merging of the Massey-Harris company and Ferguson, to create Massey-Ferguson. At that time the company's products were painted in John Deere green, this being as a result of the early prototypes being painted in the colour found in the workshop whilst John Deere products were still being serviced.

So the story really starts in Ely in the nineteen-fifties, as Peter’s fertile mind addressed the problem of mechanising the harvesting of sugar beet. Given that most beet was lifted and topped by hand, at the back-end of the year often in harsh working conditions, he was pushing at an open door.

Sugar Beet in Britain

Sugar beet had been grown in Britain since the first processing factory was opened at Cantley in Norfolk in 1924. The whole sugar industry was government sponsored because the First World War had shown how vulnerable Britain was to a cutting-off of food supplies through the submarine menace. Without sugar the country would be in serious trouble. As a consequence an ambitious plan was implemented under which 18 factories were built to process the raw sugar beet into refined sugar and its animal feed by-products.

This of course meant the crop had to be attractive to grow, and so prices were set which guaranteed farmers a good return for their efforts. The British Sugar Corporation was established, which totally controlled what was grown, how many tons each farmer could grow, at what price it would be bought, what penalties would be incurred by the growers if they did not produce the necessary degree of cleanliness and topping of the beet they sent to the factories, even indeed the days on which the Corporation wanted each farmer’s beet at the factory, and to which factory it would be sent. To help them grow the crop BSC, as it was known by all and sundry, employed field experts to advise growers on how to do the job better. Failure to comply could lead to a loss of some, or in extreme cases, the entire quota. In the bad years of the twenties it was the beet cheque that kept those farmers lucky enough to have a quota financially afloat. Few could afford to lose it.

The First Machines

At this stage beet ploughs had been around for a long time. Often horse-drawn, they simply turned the beet out of the ground, where it would be left to dry out. In due course a farm worker would pick up each beet and with a deft stroke of a sickle-like knife cut off its top. Sugar beet factories penalised farmers who sent in under- topped beet, even as they do today, so accurate topping was essential. On the other hand one did not want to cut off more top than was necessary because one would lose some of the value of the crop. Next each root was flung into a trailer, and taken off the field to be delivered to the designated processing factory, usually by rail. Remembering that this work was often carried out in the depths of winter one can easily imagine how anything which relieved this soul-destroying drudgery was sure of a welcome. Or was it.....

Hand labour still ruled the day, even after machines appeared.

Farmers were in those days notoriously conservative in their views, and with labour being paid a pittance, living as often as not in tied houses, machines that saved labour needed to do the job better than a gang of men, quicker, and preferably cost next to nothing. Well, of course machinery has its price, but this price had to be well within reach of the farmer’s pocket. Leasing was unheard of, and hire purchase viewed with suspicion. Only the bank manager was seen as a source of funds, and few wanted any higher overdrafts than they already had.

This therefore was the challenge facing the designers of farm machinery, and one that Peter Standen had to meet.

An early prototype of the Standen Beet Master:

A set of pointed discs held the top of each sugar beet plant to allow it to be cut. This was turned by the main wheel.

A knife set underneath it sliced off the top. Even today this is the best method of topping sugar beet.

Not visible in the picture are a pair of lifter- wheels that squeezed the beet out of the ground and into an elevator. The rest of the working parts are PTO powered. The most popular tractors were the 20 to 35 HP models produced by MF, Ford, David Brown and IH.

The beet was dropped into a tank at the rear of the harvester and when it was full a lever was pulled which allowed the moving floor of the tank to eject the beet in a pile on the ground.

Later machines incorporated a discharge elevator so that the beet could be delivered direct to the small trailers which were in use at that time.

These were the days before drawing aids, and engineers worked more often than not from sketches. Peter Standen would sketch out what he wanted and this was interpreted by his development people. The sketch shown below was found on the back of a photograph by the author of this history as he rummaged through an old box of photos stored in the attic of his office. It is almost certainly by Peter as no one would have dared to deface one of his precious pictures!

All the testing that took place had one end: to harvest with one machine more than one acre of beet in the day. Finally this milestone was achieved, and Peter’s son Edward remembers his father coming home one day in the fifties and announcing, "We’ve done it!" And so they had. The first stage of the growth of Standen Engineering was over.

Here are some pictures retrieved from the archives, with a few words about each.

An early prototype outside the Lynn Road premises in Ely. Although it is difficult to see, there is in fact a topper mounted on the front of the tractor. This was a novel feature which a decade or two later became standard on multi-row harvesters.

Gleave & Key in Norfolk were Standen's first dealer:

Windrowing fodder-beet for animal feed:

A topper prototype:

Delivering to dealers was often by rail:

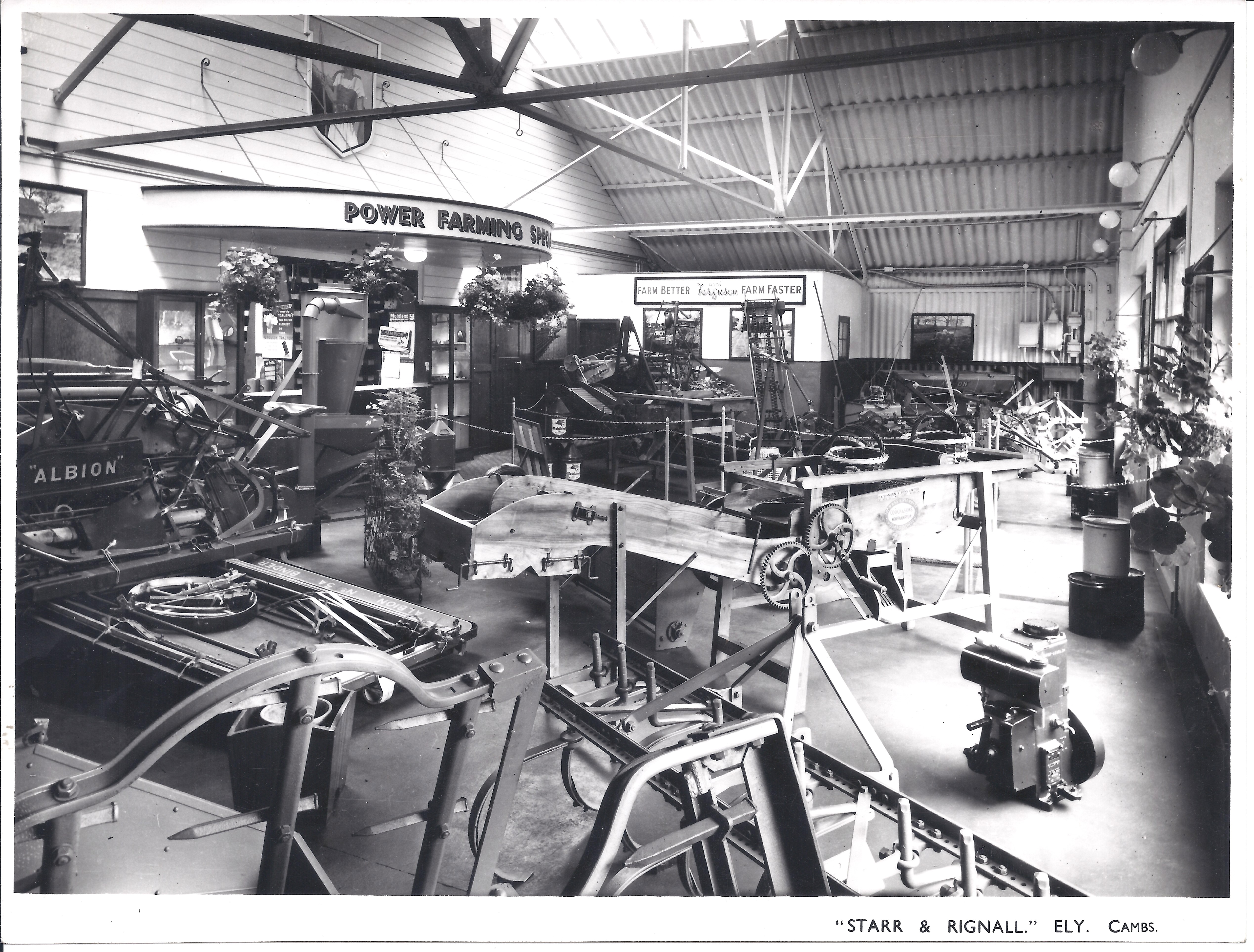

A typical dealer's show-room in 1938:

This picture shows seven different models of Standen sugar beet harvesters working in line-ahead. This was staged for a television documentary made in 1968.

In 1986 Peter Standen revisited the factory, for the first time since 1969. In this picture we see him with some of old colleagues, all but one of whom had also retired. In the picture, reading left to right, are Sid Rowe, who was the company's purchasing manager until 1977, George Gray, the development engineer who also retired in 1977, Tony Bell, who ran production, then we have Peter, with his second wife, Fay. Next to her stands Bob Baxter, Standen's sales director until 1984, and Jack Keen, who was the factory director until 1979. Leaning into the machine is Vic Grey, who worked on developments until 1989.

This was Peter's one and only visit to the company he founded after he had departed in 1969. At the time of his visit he and his wife were living in Jersey. He died on Christmas Eve 1989, peacefully in his sleep.